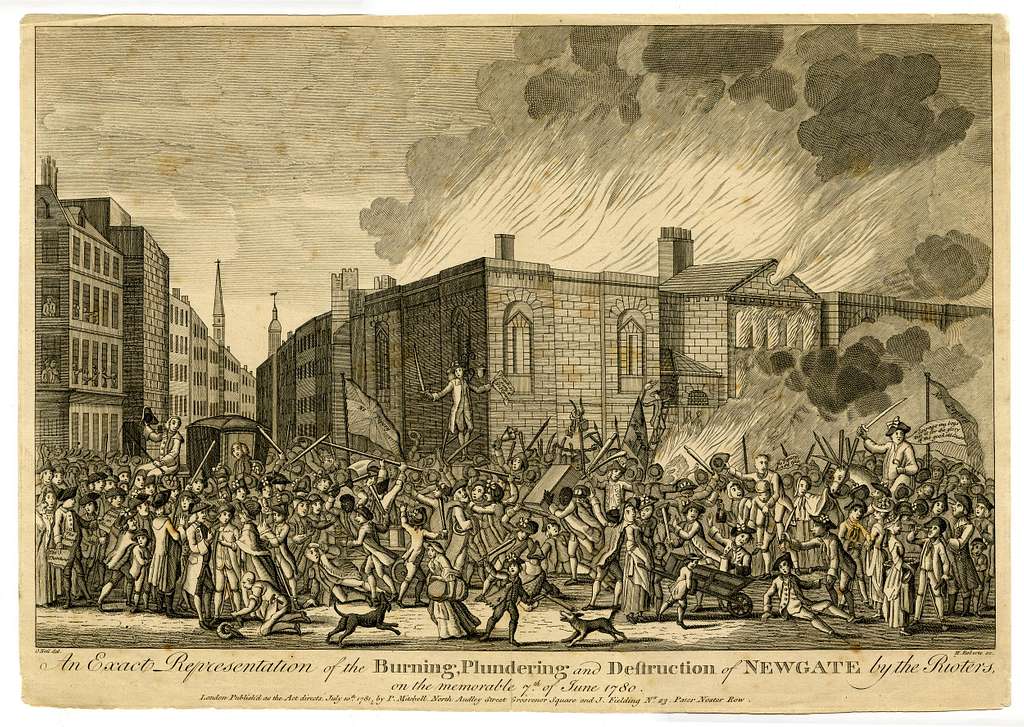

“Gone west.” Today it’s a gentle, slightly ironic way to say someone’s dead. But the phrase carries a deeper, darker meaning, for centuries in London, to “go west” meant something literal and public – a slow, often overcrowded, noisy procession from Newgate Prison to the triple gallows at Tyburn where Marble Arch now stands. That journey, part ritual and part spectacle, helped glue the phrase into the English language and imagination. Here’s the story behind those words, the carts, the last ale, the tolling bell and the Tyburn Tree itself.

The route and the ritual

If you’d lived in London between the 16th and 18th centuries, you would almost undoubtedly seen convicts loaded into open carts at Newgate, clambering onto their coffins and setting off through Holborn, St Giles and along Oxford Street to Tyburn – roughly three miles but often hours away because of crowds up to two hundred thousand. The procession was escorted by court officers, the prison chaplain (“the Ordinary”), the hangman and his assistants and sometimes even a troop to keep order.

A “last drink” (or two) was given to criminal about to be executed, with inns on the route supplying strong ale or wine to steady nerves (or inflame the crowd). The streets would swell with curious onlookers; vendors followed behind, hawking ballads, prints or refreshments

This most famously included a final dram or tankard at the provided by the churchwardens St Giles Inn, known in London slang as “St Giles Bowl” or the Angel Inn. The ritual was so common that almost every execution account mentions it. It was part punishment, part pageant and condemned people were expected to wear their best clothes and to “play the part” of the repentant sinner before the gathered throng.

The Newgate Execution Bell

St Sepulchre-without-Newgate’s Execution Handbell

The church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate was perched just outside the gates of Newgate Prison and played a dramatic role in the ceremony. In 1605, a local merchant tailor named John (or Robert) Dowe endowed a fund to install a handbell and sustain a ritual: at midnight on the eve of a scheduled execution, the sexton or bellman (some sources suggest via a crypt or tunnel under the road) would go to the condemned cell, ring the bell twelve times and recite a stark verse:

“All you that in the condemned hole do lie,

Prepare you, for tomorrow you shall die;

Watch all and pray, the hour is drawing near

That you before the Almighty must appear;

Examine well yourselves, in time repent,

That you may not to eternal flames be sent.

And when St Sepulchre’s bell tomorrow tolls,

The Lord above have mercy on your souls.”

Past twelve o’clock.

The next morning, as the prisoner was conveyed in a cart that passed the walls of St Sepulchre’s, the bellman again stood outside the church wall tolling his bell, repeating prayers and calling on the crowd to pray for the condemned.

St Sepulchre’s great bells would be rung as the execution took place, they would toll a “passing bell” – a public announcement of death in process – it was a death knell, a last spiritual summons and a public warning.

A small posy of flowers was sometimes handed to prisoners as they passed the churchyard wall – a strange mix of compassion and ritual.

The church is still there today and is well worth a visit – the Execution Bell is on display.

Tyburn Tree, the triple gallows and who “Went West”

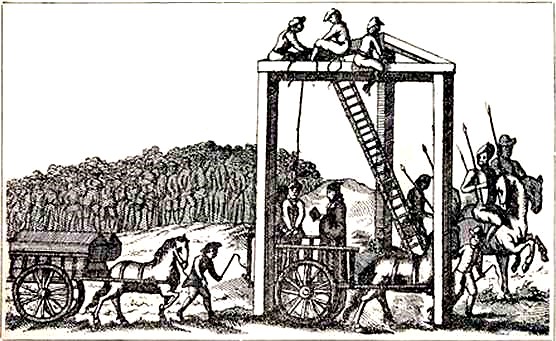

They Tyburn Tree – The National Archives (United Kingdom), catalogued under document record WORK16/376

Tyburn had long been London’s principal execution site. The first recorded hanging there was in 1196 and the gallows – popularly called the Tyburn Tree – sat at a junction near the area we now call Marble Arch. The “Tree” dominated the area for centuries. By the 16th century the gallows had been reconfigured as a “three-legged mare,” a triangle that allowed several people to be hanged at once; mass executions were not unknown (one day in 1649 saw 24 people hanged together). Public executions at Tyburn were more than punishment: they were civic theatre, medical fodder (bodies sometimes went to surgeons) and a market for souvenirs and bawdy songs. By the 1570s, records show hundreds of felons were condemned to die at Tyburn each decade – for crimes from theft to murder – and the spectacle was firmly embedded into London life.

Old Bailey research and execution registers show some 1,100 men and nearly 100 women were executed at Tyburn during the 18th century alone and a decade could see hundreds of hangings including about 300 between 1735 and 1744. The sheer scale helps explain why Tyburn became shorthand for capital punishment.

But where did “Gone West” come from?

So where does “gone west” come in? There are a few overlapping influences. Thieves’ and prison slang in the 18th and 19th centuries often used geographical shorthand for fates – and Tyburn, out to the west of the old City, was a frequent destination. Dictionaries of idiom note that “go west” in British slang came to mean “to die,” probably via “to go to Tyburn” (you literally went west along Oxford Street) and the phrase was later popularized in military slang during World War I. The image of the sun setting in the west – a poetic link to dying – probably reinforced the expression as it moved into ordinary speech. In short: a real route, a crowded ritual and the geography of London combined to turn a local fact into a lasting expression.

Once the cart arrived at Tyburn, it would be positioned under the gallows, the noose was placed, the condemned allowed a final address to the crowd, then the cart was moved away and criminal was hanged. Bodies were sometimes left hanging for hours, sometimes they were sent to anatomists for dissection, or displayed in chains at other sites.

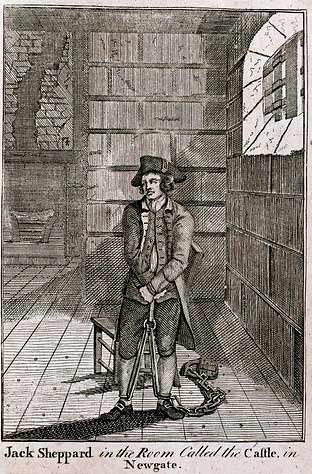

Jack Sheppard in the “Castle” Room in Newgate Prison

The Human Viewpoint

This public ritual had a human dimension. Consider Jack Sheppard (1702–1724) – the most famous escape artist of his day. After multiple prison breaks and daring burglaries, he was finally recaptured and sentenced to death. When paraded through the streets to Tyburn, as some 200,000 citizens crowded in to see him. He became a folk legend, transformed by pamphlets, plays and popular sympathy.

Another figure was Paul Lewis, a highwayman executed at Tyburn in 1763. He had once served in the navy and his trial and execution appeared in popular journals. The spectacle of his death helped cement the moral narrative from the establishment, a terrifying example to deter criminality.

Rewind a hundred years and you find Marcy Clay (alias Jenny Fox) was condemned in 1665 to hang at Tyburn for theft. According to the pamphlets of the day, she escaped death by poisoning herself in Newgate, but crowds gathered even at her deathbed. That she was a woman, a thief and defied convention made her case all the more sensational.

Perhaps the most symbolic was John Austin, who died on 7 November 1783 – the final person ever hung at the Tyburn Tree. His execution marks the end of centuries of spectacle. He was brought from Newgate by cart which stopped for the well-established rituals, the noose slipped over him and the cart was drawn away, he strangled slowly – supposedly taking ten minutes. Afterward, the gallows were dismantled and future executions were moved to the prison precinct and then inside prison walls to curb rowdiness.

When John Austin walked his last route, the tradition of execution at Tyburn ended. The cart, the route, the crowds and the tree – all were put to rest.

If you walk Oxford Street toward Marble Arch today you will see a traffic island with a plaque which simply says “The site of Tyburn Tree” where three symbolic young oaks were planted in 2016. If you walk a little further on you will see, on your right, the house of the Tyburn Convent, a cloistered contemplative Benedictine order of nuns that continue, to this day, to pray for the catholic martyrs and the many, many people who lives were taken from them there.

The phrase “Gone West” may have lost its cartwheels and its jeers, but the route that made those words forever holds the sad story of its past and the sadder story of those whose past was ended there.